Are Humans the Only Animals that Keep Pets?

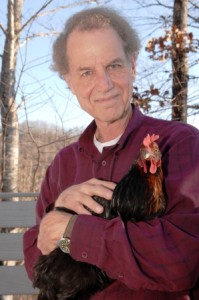

In this monthly blog, psychologist and author Hal Herzog, Ph.D., discusses some of the quirks and anomalies of our relationships to our fellow animals.

In this monthly blog, psychologist and author Hal Herzog, Ph.D., discusses some of the quirks and anomalies of our relationships to our fellow animals.

Why don’t animals keep pets?

Oh, I can already hear the howls of objections. What about Koko’s Kitten, you ask, referring to the well-known case of the American Sign Language-trained gorilla who fell in love with a kitty cat? What about Owen, the 600 pound baby hippo who became fast friends with Mzee, a 160 year old giant tortoise in a Kenyan game preserve? How about Tarra, the Asian elephant, at the Elephant Sanctuary in the hills of Tennessee, whose BFF was a dog named Bella?

You are right. There are scads of examples of long-term attachments between animals of different species. The problem is that virtually all these cases have occurred among captive or semi-captive animals in zoos, wildlife sanctuaries, or research labs. I recently scoured academic journals and consulted a host of animal behaviorists for examples of pet-keeping in other species in the wild. I found none. True, there are a few articles in primatology journals which describe instances in which wild chimpanzees “played” with small animals like hyraxes. But in each case, the relationship soon went south when the chimps killed their new pals and proceeded to toss their corpses around like rag dolls.

In his book Stumbling On Happiness, Harvard’s Dan Gilbert claims that every psychologist who puts pen to paper takes a vow to someday write a sentence that begins, “The human being is the only animal that….” I was so convinced that pet-keeping did not occur in other species that I took up Gilbert’s challenge by confidently writing in my forthcoming book on human-animal relationships: “The human being is the only animal that keeps members of other species for extended periods of time purely for enjoyment.”

But then, just days after I sent the last copy-editing changes to my publisher, I received an e-mail from my friend James Serpell, director of the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for the Interaction of Animals and Society. James, who knows that I view pet keeping as a uniquely human phenomenon, cryptically wrote, “Hal, I came across this and thought you’d be interested.” Attached was an article from the American Journal of Primatology.

Arggggh. It was bad news for my only-humans-keep-pets theory. I could almost hear James chuckling. The researchers had discovered a group of a dozen or so bearded capuchin monkeys living in a Brazilian forest who were caring for a baby marmoset, another species of monkey. The capuchins treated the marmoset (whom the scientists named Fortunata) much like Mary Jean and I treat our cat Tilley. They regularly fed the baby monkey and talk to her in capuchinese. They cradled her, carried the monkey around and let her ride on their backs during the day. And when they played with the little guy, they carefully adjusted the force of their movements so they wouldn’t injure the much smaller marmoset.

Most importantly, the friendship between Fortunata and the capuchins was not just a transient hook-up. The capuchins were systematically observed hanging out with their marmoset pal for the next 14 months.

Photos of a capuchin monkey holding her “pet” marmoset, and also giving her treats, by Jeanne Shirley.

So, has this case caused me to throw in the towel and abandon the theory that humans are the only species to keep pets? I have to admit that the capuchin-marmot relationship has caused me moments of doubt. I am not, however, ready to completely give up the idea for a couple of reasons. First, while the capuchins were not confined, the situation was not completely natural as the monkeys were given food every day as part of a program designed to promote ecotourism. Second, it is unclear whether this is a case of pet or adoption. (The researchers call it adoption, but I suppose you could also say that I “adopted” Tilley.)

Finally, Fortunata could be the exception that proves the more general rule that non-human animals don’t keep pets. Capuchins are among the smartest of monkeys and have been referred to as “the New World Chimpanzee.” Like chimps, they live in complex societies, use tools, eat meat, and have large brains in comparison to their body size. But, if capuchins can manage to bring a stranger into their lives and keep it as a pet for over a year, why don’t chimps?

I’ll take up this intriguing question in my next Zoe column.

In the meantime, use the comment box to let me know if you can think of other documented cases of pet-keeping in the wild among non-human animals.

Here are the rules: In order to qualify as a pet-keeping, the relationship must be:

- relatively long-lasting

- not have obvious benefits to the pet’s “owner”.

(And relationships between parasites and their hosts don’t count!)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Hal Herzog is a psychologist at Western Carolina University whose research focuses on our attitudes towards and interactions with other species. His book Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It’s So Hard to Think Straight About Animals is published by HarperCollins.