How Smart Is a Dolphin?

Dolphins and UsPart One: The Smartest of Us All? “So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish!” Amazing Abilities of Dolphins Dolphins or Humans: Who’s Smarter? Dolphin Society and Culture They’re Super-Brainy, Too More Fascinating Stuff The Great Researcher A Society that Works Are Dolphins “Persons” Life and Culture How Smart is a Dolphin? Experimenting on Dolphins My Visit to the Dolphins Other Links & Videos Mirror Self-Recognition Test The Herman Investigation The Minds of Whales |

What does the dolphin brain tell us about their intelligence?

While there are big differences between dolphins and humans, our brains have much in common. Dr. Lori Marino is the world’s expert on dolphin brains. (She only studies the brains of dolphins who have died – and died naturally.)

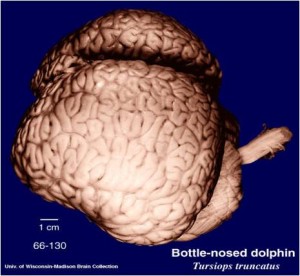

It’s fascinating when you compare the dolphin brain and the human brain. You can see they’re both big and complicated, but they work quite differently.

Dr. Lori Marino: Yes. They represent two different ways that one can be really intelligent. The part of the brain that’s most involved in thinking and intelligence is very different between humans and dolphins.

Which part is that?

L.M.: It’s the neocortex – the outside covering – and it’s an evolutionarily recent part of the brain. It’s basically a sheet, what you’re looking at on the outside that’s all wrinkled. If you were to unfold it, it would be a long thin sheet. The more folds there are, the more surface area there is.

The dolphin brain looks like it has more folds than the human one.

L.M.: Well, they’re different in a number of ways. The human neocortex is thicker, but the dolphin’s is more convoluted and has greater surface area. The human way is to have a thick one, and the dolphin way is to have a thin one but many more folds.

What does this tell us?

L.M.: Both brains have undergone a tremendous amount of elaboration during their evolution. But during the past 50 million years or so, dolphins and whales have been evolving in the water, so the brain expansion has taken a different trajectory. It represents a different neurological scheme for intelligence. It has many of the same sorts of functions, but they’re designed differently. The whole map of the brain is different.

What might that tell us about how dolphins think and feel?

L.M.: There’s a lot we don’t know, but we do know they’re capable of very complex intelligence. And the parts of the dolphin cortex that are involved in things like processing sight and sound are really close together. They have a different sensory map, a different way for their senses to relate. It might have something to do with echolocation because they have to be able to think auditorially and visually almost simultaneously. But there’s much more to it if you go below the neocortex – all kinds of complex structures that have to do with memory, emotions, social information and other kinds of behaviors.

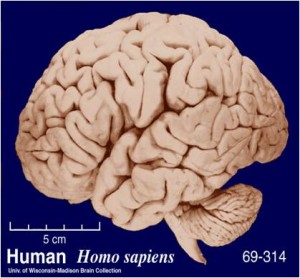

Cross-sections of the dolphin brain (left) and the gorilla and human brains (right).

Now, looking at the next two pictures, one says “Gorilla/Human Brain,” and the other says “Bottle-nosed Dolphin Brain.” To me, they’re just a bunch of different dots on the page, but to you this means something very significant.

L.M.: Yes. These are cross-sections through the neocortex. You’re seeing different layers of cells. In primate brains, there are six identifiable layers. When you go over to the bottle-nosed dolphin, there are only five layers and they don’t have the same arrangement that primates do. That means they have a completely different way to process information.

It’s strange to think that we’re two entirely different species …

L.M.: … Our common ancestor lived about 95 million years ago …

… and we went in completely different directions, but that we come back together and we’re talking to each other today. And the idea that we can even understand each other, that there’s so much in common, is amazing.

L.M.: It’s an amazing convergence. What would be the odds that there would be anything much in common when it comes to higher level cognition?

What we’ve learned from captive dolphins and why we must stop

You spent some time with Professor Lou Herman, who did some of the most advanced work on dolphin intelligence and understanding. What did we learn from him?

So we’ve learned that they are about as intelligent and self-aware as any other being on the planet. So, ironically, hasn’t he just proved that dolphins should not be in captivity?

L.M.: That’s right. And that’s why I stopped doing work in captivity. After we did the mirror self-recognition study, I understood that I had to respond in an appropriate, ethical way by no longer supporting the continuing exploitation of these animals. What Lou’s lab has shown has come at a terrible price for the animals. Even though we have learned a tremendous amount, it hasn’t translated into anything that helps dolphins in the wild. The most fascinating work today – and actually all along – is being done in the field. You can learn a great deal about these animals if you go to them.

So we’re not learning anything anymore from dolphins in captivity.

L.M.: No. That line of research is pretty much a dead-end.

When you say that the knowledge gained by Lou Herman came at a terrible price, I’ve heard that they all died prematurely and from sicknesses they might not even have had in the wild.

L.M.: That’s right. They all died in their 20s and they didn’t live the natural life span or the quality of life that they would’ve had in the wild. The same is true of the two dolphins I worked with at the New York aquarium on the self-recognition study. They both died prematurely as well. So, when all the research subjects have died prematurely, that should tell you something. It certainly told me something.

How come it doesn’t tell a lot of other people something? There are research labs and aquariums with so-called research going on all over the country and around the world, and with scientists who are all aboard the captivity routine. But I couldn’t get them even to say what they think about keeping dolphins in captivity.

L.M.: I think a lot of that is due to blind ambition. The scientific field is extremely competitive. Most people don’t want to offend anyone they might need for a grant or a recommendation. They become cowardly. They basically decide that their research career is more important than doing the right thing. You make a choice, a conscious choice.

Dolphins in the wild

What are some of the things you’d like to know from dolphins who are being studied in the wild?

L.M.: I would love to know what they actually think, how they see us, how they think about us, how they feel about us. And as a scientist, I’d like to know more about how they communicate. We’re still so far from understanding that now. We haven’t even scratched the surface.

What do you think they think of us?

L.M.: When I was still interacting with dolphins in captivity, they seemed to have sort of a one-up attitude toward us. They’re very clever, very sly in the sense that they like to test us to see how intelligent we are. I’ve also been out with dolphins in the wild, and they seem to care very little about what we’re like. They’re curious about us, but they seem to be … just curious.

One thing I would like to understand is that if they’re so intelligent, why do they still hang around at places like Taiji in Japan where they’re going to get rounded up and massacred? Why hasn’t word gotten around, do you think, that says: “Hey folks, get out of here”?

L.M.: I think one reason is that when the fishermen round up a group of dolphins, typically no one escapes. So there’s no one to tell the others. Also, the dolphins have migration routes that are very important to them, and it may not be that easy to just change those. But we do know, for example, that dolphins have learned about tuna nets. They’ve already adapted, so when they get caught in tuna nets, they don’t panic as much. They’ve learned that they can just wait and be let out of the net or jump over the net. And there are places in Japan, like in Futo or Iki Island, where people used to capture dolphins and today there are no more dolphins. This could be partly because they’re taking a different route.

Of course, when you ask that question you should bear in mind that we humans keep making the same mistakes over and over and over again. When you look at how many people die in car accidents or get hit by cars in the street, someone observing us from the outside would look at us and say …

… that humans are quite stupid! What are one or two of the ways you would say dolphins are probably smarter than us?

L.M.: They’re probably more socially complex than we are. They’re certainly more social than we are in the sense of being tuned in to each other. When you work with them, you’re always catching up to them. If you’re working with them in captivity and you give them a task, they get it right away or they’re trying different things out to figure out what you want. They’re always one step ahead of you. They’re quicker on the up-take.

Why would that be?

L.M.: Well, they don’t have the luxury of a terrestrial mammal – being able to go up a tree or into a cave or dig a hole. They have to react to things very quickly. The only real support they have is from the group. In order to keep the group together, they have to be very in tune with each other. They use synchrony a lot in their behaviors. When you see dolphins diving synchronously or spy-hopping synchronously, they use that as a form of social cohesion. They really understand timing very well. And when one dolphin mimics another, you see that they’re very fast at reading subtle cues and dynamic signals. They have to be because they live in a dynamic world.

When you see people doing synchronous swimming at the Olympics, you know it’s taken them years to be able to pop out of the water at the same time. Dolphins figure out new synchronous swimming techniques in seconds.

L.M.: They just do it naturally. They do synchronous swimming all the time.

What makes you such an advocate for dolphins?

L.M.: When I saw the videos of the Taiji and Faroe Island hunts, it was just a question of what can I do? This is wrong and I have to do something. And the fact that I study them means I can apply my expertise and my reputation to the issue and that helps.

What can we all do to help?

L.M.: We can stop supporting the captivity industry.

That means not going to the SeaWorld shows?

L.M.: Not going to marine parks, entertainment parks, swim programs, so-called dolphin “therapy” programs, because all these places are responsible for exploiting these animals and confining them in ways that are just horrific for them. Even if we were getting incredible science out of it, it wouldn’t be a good reason. The fact that we’re getting no science out of it makes it totally unjustifiable on all grounds. The easiest thing anyone can do is decide to do something else for their vacation instead of going to see orcas flipping or going to swim with animals at a resort.

These places depend entirely on ticket sales. So the public is actually keeping all of this going. And when you buy a ticket to an entertainment park like that, you’re also supporting drive-hunts all over the world. If people could actually just see those drive hunts and what it’s really like for dolphins in captivity, I don’t think they would want to support these places anymore.

What if I’m a parent and I’m thinking that it’s good for Johnny to see dolphins close up because it will give him an appreciation of nature? What could Johnny do instead?

L.M.: There are animals all around him all the time. But if you want to get closer to dolphins and whales, you can go to a reputable eco-tourist place where they go out in boats, or you can even charter a boat yourself. You have to observe a lot of rules, like not harassing them or even touching them, and there’s no guarantee that you’re even going to see them, but you can go to them. I’ve been whale watching; I’ve seen incredible things from a boat. You get a completely different idea about the animals that way. In fact, the dolphins in captivity and the dolphins I’ve seen in the wild are like two different animals. I wouldn’t want a child to be exposed to these marine parks. I’d take them out on a boat, or watch a film about it.

But the other thing, too, is that you don’t have to see everything in order to appreciate it. You know, kids love dinosaurs. They love them. I mean, it’s an obsession; they are mesmerized by them. But no one has ever seen a dinosaur, petted one, or rode on one or received “therapy” from one. There’s a lot of things in life you don’t get to see, and that’s just fine.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Dr. Lori Marino is a senior lecturer in neuroscience and behavioral biology at Emory University. She is also the founder of the Aurelia Center for Animals and Cultural Change.